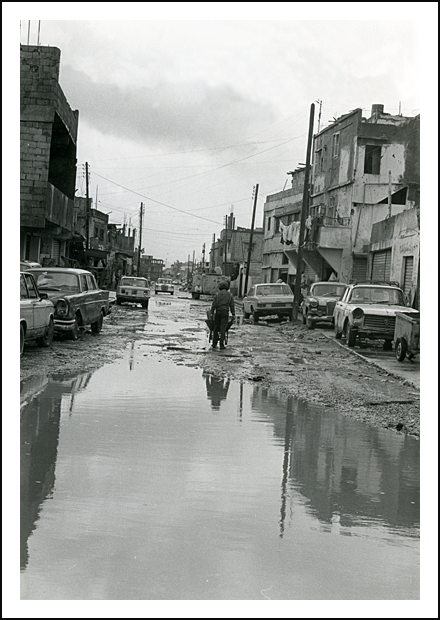

A view of the main road beside Shateela camp, looking southwards.

(Taken during the winter 1982 - 83).

Photo: Rosemary Sayigh

|

A view of the main road beside Shateela camp, looking southwards. (Taken during the winter 1982 - 83). Photo: Rosemary Sayigh |

|

load helped to expel worry. She'd be awake by 4am most days of the week, either to heat water for washing clothes, or to mix the ingredients for bread making. As long as I've known her she has made bread at home - a task that takes several hours between mixing, shaping the balls of dough, rolling them flat, stacking them between layers of cloth, and sending them to the baker. In the year after the massacre, with electricity and water supplies in the camp not reconnected, Umm Mustafa had to carry - with her daughters - all the water needed daily for cooking, drinking and washing from a street tap, and pour it into big barrels stacked at the entry to their building. From there it was hand pumped up to their apartment on the 4th floor. After that she did the shopping in Sabra for fresh vegetables and fruit, and cooked the family's main meal of the day. In the afternoons if she didn't have a class, there were visits. Her oldest child, Aida, was only 16 and still in school, so that most of the burden of housework fell on Umm Mustafa. What made things harder for her was that she had no female relatives in the Beirut area. Her family was from Aqbara in Palestine, and they were all concentrated mainly in Nahr al-Bared and Ain Helweh camps.

The period after the invasion and massacre, with the Israeli army occupying South Lebanon up to the Awali River, was a time of fear and suspicion. When even neighbours could not be trusted, it was difficult to explain to people what I was doing there in Shateela camp. A study? What could I possibly want to study at a time like this? Most people were too angry or too fearful to talk to me at all. If I asked anyone the simplest question, such as 'What is your name?' or 'What village do you come from?' they would say, 'Why do you want to know?' Why indeed? I was careful not to write any notes while in the camp, in case I might be searched at the Army checkpoint on the way out. Umm Mustafa defended me to her milieu with quiet authority, 'She's a friend of the Palestinians'. I recorded a few massacre testimonials. But it was still too soon for such work, memories were still too close and raw, it felt bad doing it. I accompanied Umm Mustafa on visits, in the afternoons, just as I had |

done with Umm Hussein, and Umm Joseph; but her visits were more confined to the camp and its immediate surroundings. She liked to visit the homes of her students in the adult literacy class. Some of these were from gypsy families, who had their own 'colony' in the Hursh, a target of the massacre perpetrators because they were known to work with gold. Others we visited were Shi'ites from the South, and Palestinian refugees from Tell al-Zaater. We visited people who were quite well off, and we visited people who were among the poorest in the area. Umm Mustafa's visiting crossed ethnic, class and party lines. Though she was a 'friend' of her husband's faction, the PFLP, her visiting wasn't restricted to them.15 If I ever asked her why we were visiting so-and-so the only explanation she'd give me was, 'They are good people'.

Whenever I stayed overnight in the camp, Umm Mustafa would lay out a mattress on the floor of the sitting room where the TV was, and sleep beside me. I think this was normal practice for looking after passing visitors, transmitted from a recent past when both rural and urban people moved around constantly, staying with relatives or friends or trading partners. I felt very lucky to have Umm Mustafa as a friend: she was widely respected in the Shateela community not just as a 'mara nasheeta' (active woman, patriot), but also as someone wise and honest, who gave good advice. She never slandered people, or gossiped. She skillfully held a middle ground between her husband's minoritarian left-wing views and the Muslim nationalism (or nationalist Islamism) of the majority. She was quite highly educated for a camp woman of her generation, and could speak knowledgeably about politics.16 She always welcomed me warmly when I visited, and took a helpful interest in my research. It was a great loss to me when she was forced to leave Shateela after her home was completely destroyed in the first battle of the camps (May-June 1985). The tenement building had been an easy target for Army shelling from the Sports City, and was destroyed beyond repair. Abu Mustafa stayed in the camp but the family went to live near Sidon, too far away for daily visits.

|

|

15. Many women did not join Resistance groups as members but supported them as ‘friends’, carrying out auxiliary activities (Sayigh and Peteet 1986: 118-121). |

|

16. Umm Mustafa had completed the full UNRWA school programme, at a time when girls were usually withdrawn after a few elementary classes. |

|

Copyright©2005 |

|