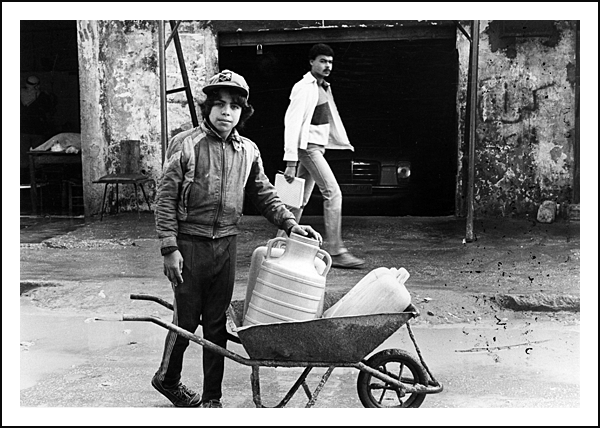

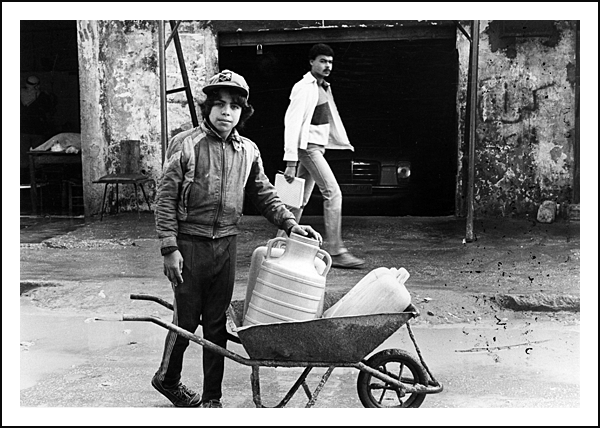

This boy around 11 years old lost his parents in the Sabra/Shateela massacre

and became responsible for his younger siblings. He earned money by carrying water.

Photo: Rosemary Sayigh

|

This boy around 11 years old lost his parents in the Sabra/Shateela massacre and became responsible for his younger siblings. He earned money by carrying water. Photo: Rosemary Sayigh |

|

autonomous, yet they allow greater scope than interviews do for speakers to choose what they want to say, and not to say, and how to say it. The indirectness of the life story as research method, the scope it gives to speakers to represent both 'self' and collectivity, encouraged me to extend the method to Palestine itself, a project that was the first step towards this archive. Recording produces tangible records of refugee experience - still lacking in the writing of Palestinian histories.

It would be hard to over-estimate the influence of these three women - Umm Joseph, Umm Hussein and Umm Mustafa -- on my life and work. And though I never knew her, the idea I formed of Umm Yusif from what others told me remained a live grain within my psyche. Because of these women, I could never have approached Palestinian women simply as victims, whether of Israeli aggression or Arab societal patriarchy. Nor could I view them as in need of 'empowerment' from Western women. Objectively I could understand that I was freer of social constraints than they, luckier in terms of nationality, class and education. But they had kind of power that I found not only impressive but lacking in myself and most 'liberated' women, the power to make others in their immediate environment pay them attention, even obey them. They could produce outcomes they desired - one possible definition of power. Of course their desires were constrained by their upbringing and cultural environment, but then so is everyone's. It's difficult to analyze exactly what their power is based in, and certainly it took a different form in each of these four women. If forced to define it I'd say it was partly based in a highly developed concept of maternal responsibility; partly in a technique of expressing 'self' (as personal rights) in balance with a host of collective claims on the individual -- so many that constant balancing between them becomes a fine skill; and partly in the rapid understanding of other people that subordination generates. But this is only a beginning of explanation. Their value for me has not lain in the information they have given me, or the way they helped my research. Much more it has been their model of |

courage, tenacity, resourcefulness and humour. Though all were victims of expulsion and of gender subalternity, I would never think of them primarily in these terms, but rather as people who knew/know how to live against poverty and oppression.

The story of the voice archive One part of this story remains to be told, the genesis of this archive, recordings made between 1998 and 2000 in different regions of historic Palestine (Gaza, the West Bank, Jerusalem and '1948 Palestine' or Israel). The narratives of women from Shateela and these later stories of displacement from and in Palestine are thematically connected but methodologically distinct. I left the Shateela speakers free to tell their 'life story' as they wanted, without the imposition of any topic, framework, or beginning; whereas with the recordings in Palestine, I based the project explicitly on the experience of displacement. I did this not just through a statement of research aims that mentioned 'tahweel' and 'tahjeer' (displacement),22 but more strategically through a search for speakers who had been displaced in any one of several different ways - expulsion, deportation, destruction of home, imprisonment, etc. Indeed one of my research aims was to see how many forms displacement could take. This shift was introduced because I had come to the conclusion that displacement was the defining experience of the Palestinian people in modern times. The aim of the voice archive would be to offer evidence of different forms and contexts; how women have experienced displacement; how they narrate it; how they integrate displacement into larger narratives of 'destiny'; and how their stories differ from those of men. A crucial trigger of the archive project was a book by an Israeli psychoanalyst, Michael Gorkin, entitled Three Mothers, Three Daughters.23 A lively and readable book, it illustrates deeply held misconceptions about Arab and Muslim women, and about the recent history of the Arab region. Though it tells us much about Palestinian women's reactions to their familial and local context, it totally lacks their overall context of dispossession and statelessness. Such a focus distorts. The author selects a priori just three aspects of women's lives: i) levels of education;24 ii) degree of freedom |

|

22. ‘Tahweel’ means literally ‘movement’ or migration; ‘tahjeer’ is more accurate because it expresses the idea of coerced migration, ie. displacement. |

|

23. Gorkin 1996. |

|

24. "Perhaps the single most striking measure of change in the lives of women in Palestine has been the enormous increase in educational level over the last half-century" (Gorkin 1996: 2). |

|

Copyright©2005 |

|