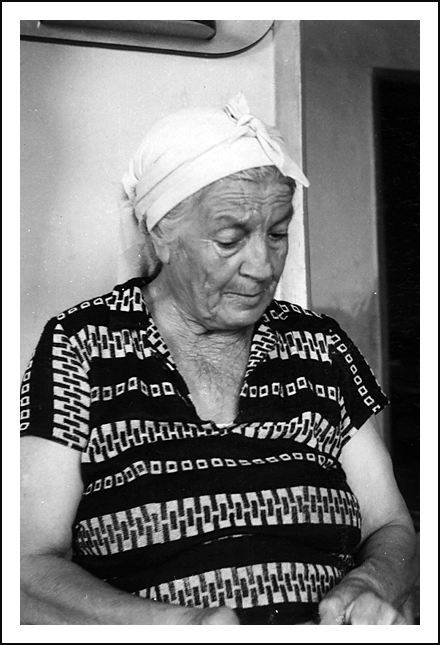

Umm Joseph. Dbeyeh camp, 1970.

Photo: Rosemary Sayigh

|

Umm Joseph. Dbeyeh camp, 1970. Photo: Rosemary Sayigh |

|

tric-trac. Umm Joseph once told me that from the beginning she had worked to save Abu Joseph from the humiliation of doing work below his dignity. Lebanese law blocked the refugees from semi-skilled jobs as well as the 'free professions'. They were not allowed to be drivers or guards or employees in large foreign companies, though some managed to do such jobs illegally. So Umm Joseph worked in houses - like many other refugee women of her age - because older men couldn't work, because refugee rations were never enough, and because children had to be educated beyond what UNRWA offered free. Another reason - never stated -- was so that her only son Joseph's wife could stay at home with the children. Young mothers, or girls who had left school but hadn't yet married, were only allowed to work outside the home if there was absolutely no other source of income. If you asked people, they would say, "This is part of our tradition". But unmarried women had begun to work in Palestine before 1948. Probably rural refugees sensed the Lebanese atmosphere as deeply alien and threatening, and reacted to it by stiffening their 'difference'.

First fieldwork in Dbeyeh camp: Umm Joseph By the early 1970s I was back to university, taking social science courses at the American University of Beirut, and wanting to do research about Palestinian refugees. To practice 'fieldwork' I began making longer visits to Dbeyeh camp, staying with Umm Joseph for periods of up to a week. At that time her household consisted of herself and Abu Joseph, their daughter-in-law, Leila, and Leila's six children. The camp in those days consisted of ten or eleven rows of zinco-roofed huts stepped into terraces carved out from a rocky hillside. Overlooking the camp, on the peak of the hill, stood a Maronite monastery, the Deir that had donated the land on which the camp stood. The population was not large - hardly a thousand - and consisted mainly of old people, children and women. Most men of working age were away in the Arab oil |

countries, earning money. They came home on family visits once every two years. This was the case with Joseph, Umm Joseph's only son. Endowed with a secondary school funded by the Pontifical Mission, Dbeyeh young men had a head start over other those of other camps in obtaining the diplomas needed for salaried work.

Though their Lebanese Maronite neighbours had welcomed the refugees from al-Bassa as fellow-Catholics when they first came in 1948, by the late 1960s tension was palpable. As the feda'yeen began to carry out operations from south Lebanon, supported by the 'opposition' groups that formed the Lebanese National movement, Palestinians living in Maronite-dominated areas like Dbeyeh felt increasingly threatened. Lebanese nationalist parties had begun to form militias which vowed to discipline the Palestinians. Dbeyeh's location generated violence even before the Civil War of 1975-76 broke out. In 1973, Hanneh, a thin, sad-faced woman always dressed in black, was shot by a sniper on her way to work as a cleaner in Beirut. After the Civil War began, Dbeyeh camp was one of the first to be over-run by the Christian militias. Twenty seven years after their expulsion from al-Bassa, Dbeyeh's people escaped massacre to squat in empty buildings in West Beirut, second-time refugees. But in 1970, this future disaster was only predicted by the few old men in Dbeyeh who read the Lebanese newspapers. Women's daily routine of shopping, cooking, cleaning and visiting laid a reassuring surface of normality over premonitions and fears. In spite of her arthritic legs, Umm Joseph insisted on taking me on visits to other camp households, in the afternoons, when the day's big meal was over and all the housework done. I would have gone on my own, but this would have upset her sense of propriety. I think she enjoyed the visits. Moreover, there was absolutely no other source of entertainment in refugee camps at that time. Poverty ruled out trips to the |

|

Copyright©2005 |

|