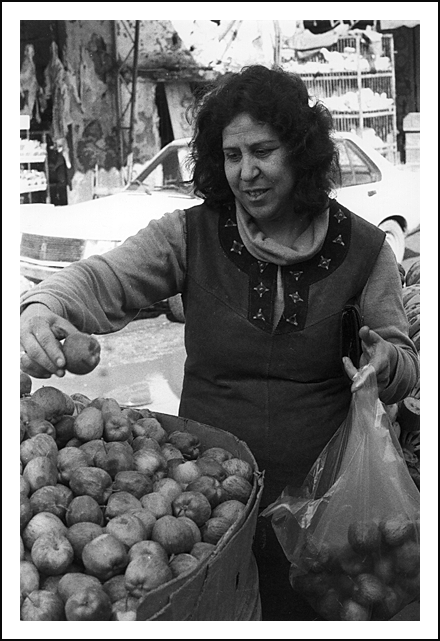

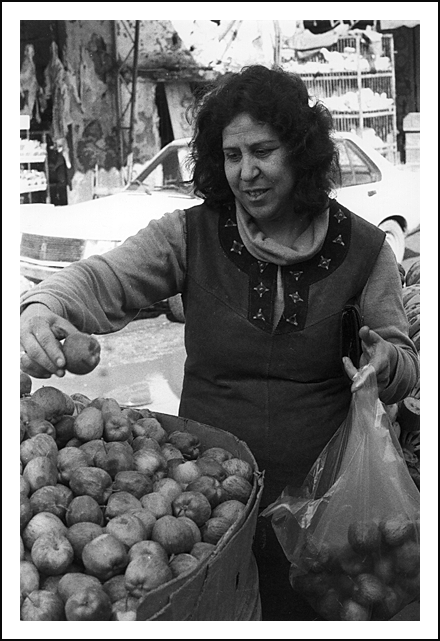

Umm Mustafa (Shateela camp) shopping in Sabra market.

Photo: Rosemary Sayigh

|

Umm Mustafa (Shateela camp) shopping in Sabra market. Photo: Rosemary Sayigh |

|

national cause, city people and rural people appeared separated in culture and mentality. But though city women might wear Western fashions and speak 'educated' Arabic, they were close to the young women of the camps in the gender conservatism of their families. The only easy pretext for a life outside the home was the same for them as girls in the camp - education. For the middle class girls who were more rebellious, or those with more liberal parents, two other openings were possible: employment and national activism. Such limited freedoms did not exist for young women in the camps, though they had an enthusiasm for the Resistance movement that partly sprang from the close control they lived under.9 A daring few joined the Resistance groups and formed the vanguard whose work became to mobilize the women of the camps. I was to meet many active women cadres in Shateela a decade later, but in Bourj Barajneh in the early 1970s they were inconspicuous to the point of invisibility. But it was in Bourj that I began to be interested in class and gender boundaries within Palestinian refugee as well as broader Arab society.

My visits with Umm Hussein ended a year before the outbreak of the Civil War, when I finished the interviews for my thesis. As Christians and Muslims began to feel insecure in 'mixed' areas, Umm Hussein was invited to care-take the house of a Christian friend in the nearby 'mixed' suburb of Haret Hreik. By this time all but one of her children had got married and left home, scattered between Abu Dhabi, Australia, Kuwait, and West Beirut. A decade later, during the 'Battle of the Camps', Haret Hreik became the scene of a massacre of Palestinians by the Shi'te militia Amal, and Umm Hussein moved to a more solidly Sunni Muslim area, Tareek Jdeedeh. Her home in the camp has been rented out to a kindergarden, but she still regularly visits her family and friends there. Since I first knew it in the 1970s, after so many wars, and a hardening of state policies towards the Palestinians, the camp has become more crowded, more miserable, and even more futureless. It's incredible that a refugee camp can get worse; but this has been the case with the camps in |

Lebanon.10

Shateela: Umm Mustafa The third Palestinian woman who impressed and influenced me was Umm Mustafa, a resident of Shateela camp. I met her for the first time shortly before the Israeli invasion of 1982, during the official opening of a PFLP kindergarden. It was situated not far from the five-floor tenement building where Umm Mustafa lived with her PFLP cadre husband and their children. Both the kindergarden and the tenement building were just outside the limits of the tiny camp, which is less than one square kilometer in size and exceptionally crowded. Because of its closeness to Beirut, many head offices and institutions of the Resistance movement were located in or near Shateela. This was the reason it was targeted for Israeli and Lebanese attack. I met Umm Mustafa the second time towards the end of the 1982 war but before the massacre, when she and her children were staying in a secondary school in West Beirut with others displaced from the war front. I found her there while helping to distribute supplies. Early in September, the school was emptied of displaced people, since the war was supposed to be over, and the school year was about to begin. So Umm Mustafa returned home to Shateela, near where a narrow road divided the camp from 'Al-Hursh' ( the forest), a once wooded no-man's land where displaced Lebanese Shi'ites and Palestinians had built squatter shacks. When the massacre perpetrators entered the Sabra/Shateela area on September 16, in the late afternoon, their first entry points were from the south, from Al-Hursh and nearby Hayy Ursan, and it was here that they 'worked' for the first day and a half of the massacre, before coming to the edges of Shateela camp late in the evening of the 17th.11 Umm Mustafa got news of the massacre from a neighbour, and succeeded in escaping with her eight children - the youngest was still suckling - from the only way out of the camp that was still unblocked, on the northeast. Israeli forces were posted on all the main entry/exit points, to turn back all who tried to leave. They managed to reach the relative safety of a mosque on the |

|

10. See the Journal of Refugee Studies 1997, especially the chapter on Socio-Economic Conditions. See also Sayigh 1994; Sørvig, op cit. |

|

11. For the massacre see Kapeliouk 1982; Genet 1983; al-Shaikh 1983; Barrada 1983; Sayigh 1994:117-122; Cobban 1984: 129-130; 117-122; al-Hout, 2004. |

|

Copyright©2005 |

|