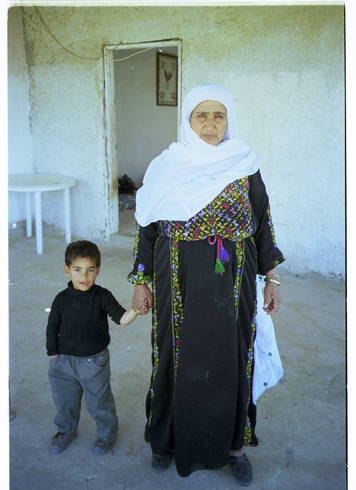

Hajji Miriam al-Sanaa with a grandson, Laqiya (Naqab), March 2000. Photo: R. Sayigh

|

Hajji Miriam al-Sanaa with a grandson, Laqiya (Naqab), March 2000. Photo: R. Sayigh |

| Hajji Mariam al-Sanaa, Lakiya village (Naqab), March 27, 2000:

|

|

Hajji Mariam is Hassan's aunt and neighbour, a strong woman who has raised ten children through her own work. She tells me that her husband was 'no good', and affirms that women are better and stronger than men. She was one of the Weaving Project's first weavers, and there's a photo of her in their catalogue. She allows me to take her photograph, sitting on a sofa beside one of her grandsons.

She gives a clear and detailed account of how life was before their uprooting, and how it changed. I'm happy that she asks for a copy of the tape, though when I listen to the recording later I'm disappointed because something about the shape of Hajji Mariam's room - maybe the height of the ceiling - has reduced her voice. Afterwards Hassan tells me that she lost a son at age 18 from lung sickness. This sad episode is not included in her narrative. In general women I've recorded with in 'Israel'/'Palestine' don't speak of family tragedies such as children who have died, in contrast with Palestinian women in Lebanon, who usually include each sad event in their narrative. There aren't enough cases to confirm the idea, but I wonder if this difference indicates meta-narratives to which individual speakers unconsciously conform. In the case of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, such a meta-narrative could be called a 'chronicle of woe', whereas anywhere in 'Israel'/'Palestine' it is one of 'survival against the odds'. Hajji Mariam begins speaking: |

to carry water, we had oxen to plough the land. We lived from our herds. We sheered the sheep, and from the wool of the sheep and the goats we made the walls of our houses. The cattle were like the cars we use to travel nowadays. If someone wanted to travel, he'd go by camel. If someone wanted to travel, he'd ride a horse. True? And we drank water from the wells. Everything was there. But everything needed effort. We drank water from the wells, from the rainwater when it rains. Everyone had a well, they maintained it and cleaned it. They'd drink from it in summer. We have a well here [in Lakiya] that is renowned (glorious). This well is ours, it doesn't belong to the Jews, it was for our ancestors. This well has water from a spring, the spring of Lakiya. And we also have our own [family] water well. We lived from the land, we sowed wheat, we sowed barley, we sowed lentils, we sowed peas. In summer, this land which you see in front of you, which is now all houses, we used to sow it for the summer with tomatoes, bamieh, water melons. We harvested them in summer. We made two dams. We sowed. All our living was from the land. (You remember this?) I remember. I remember the day the Jews kicked us out of Lakiya..." 15

In the evening Hassan takes me to a meeting which is part of an ongoing dialogue between Israeli academics from Ben Gurion university and local Palestinians. Isma'il Abu Sa'd, head of the Bedouin Studies Programme at Ben Gurion is among those present. Several local people speak forcefully in fluent Hebrew. I meet an Israeli woman, Hagar, who is living in Lakiya and doing anthropology. We try to arrange a meeting but since neither of us has cell phones the attempt fails. |

Hajji Miriam al-Sanaa with a grandson, Laqiya (Naqab), March 2000. Photo: R. Sayigh |

[Return to Jerusalem] [Hajji Umm Ibrahim al-Sanaa] Copyright©2005 |

|