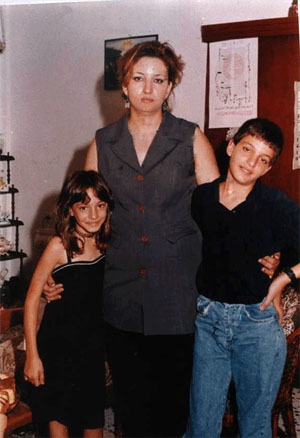

Rawiya Saffouri Shanty with her son and daughter

|

Rawiya Saffouri Shanty with her son and daughter |

| Rawiya Saffouri Shanti, Shafr Amr, April 13:

|

|

Rawiya picks me up from a bus stop in Nazareth, a tall, blonde, youngish woman with a Peugeot. She's a bit upset with me when she sees I'm not carrying an overnight bag -- she had invited me to spend the night with her, says her children are excited about meeting me. I explain that Wakim Wakim, chairman of the Committee for the Defence of the Uprooted, will be at a meeting tonight at the Tawfiq Ziyad Cultural Centre in Nazareth. A lawyer in politics, he's hard to get hold of. Tonight may be my only chance to meet him. He's from my mother-in-law's village, al-Bassa, the scene of much of my husband Yusif's childhood, destroyed after 1948.

We drive to Shafr Amr, another 'village-town' (too large to be a village, without the amenities that define a town). It has a large fir forest skirting one side of it, a wild hill-side above, and rolling green lands all around. This pleasant greenness is the result of Israel's policy of limiting Palestinian residence space and demographic growth. Rawiya says there's no profit in agriculture these days. The economic situation is bad, people have no buying power. Rawiya prepares carefully for the recording, first asking about my aims, how I define 'tarhil' (displacement, transfer), and whether I include 'domestic oppression' (itihaad) in my research? I say that the definition of 'tarhil' is purposely not fixed so that speakers can interpret and develop it in any way they want. We take this quiet moment to record, before Rawiya's children come home from school - she has a daughter and a son - in a sitting room decorated with paintings by Fathi Ghaben, an Israeli Palestinian painter whose work I've never seen before She records a strong feminist/nationalist self-narrative that shows how her ideas have grown out of experience, and how she has based decisions about her life on her ideas. Herself brought up in a 'single mother' household, she is currently going through the process of divorce. She forcefully expresses her hostility to 'traditional' Palestinian ideas about gender - that "a girl is shame, her body is shame". Equally forceful is her condemnation of Israel's treatment of Palestinians. I discover that as well as having a job and studying a branch of social science, she has been interviewed on TV. But though including Rawiya stretches my sampling choice of 'unknown women' (especially as she didn't spend very long in prison), I'm happy to have found someone young who 'lives' the Nakbeh in its consequences today rather than recalling it as a past event, someone moreover who has refused to subordinate gender to national oppression. She says that the day that Arab women bring up their children with 'full consciousness', then Israelis will be afraid. She refuses to use the word 'shame' to her daughter, allowing her the same freedom and ambitions as her son. Rawiya begins speaking: |

I don't know how it will help your research but I hope you will succeed in it. I'd like to start from my childhood years. From the time we were born we were hearing - we were raised hearing the stories of our grandmother and grandfather about the British mandate, about the Jews, Zionism, and occupation. How they entered their village, how they blew it up, how they killed and assassinated people, how they uprooted them. They told us about the agents, the people who used to inform the Jews about Palestinians, where was the revolutionary. They told us about all this. I remember many stories that were good for me to hear. These stories influenced my personality, my make-up today. I grew up with a single mother because my mother separated from my father when I was seven years old. Our household - we were eight brothers and sisters, six girls including me, and two boys. We all reached university... "

We finish recording and have lunch, the children come home, and I photograph them in the doorway of their home. Then we all get in the car and Rawiya takes me on a drive around Shafr Amr, not just to see the panoramic views but also to visit 'illegal' Palestinian villages in the vicinity. One of these is Umm al-Sahili, just six homes, inhabited by people of bedouin origin who settled there before 1948, and possess a 'tabu'. A nearby Israeli settlement, A'idi, built in 1980 on land confiscated from Shafr Amr, is expanding towards Umm al-Sahili. Three homes there were demolished two years ago, and rebuilt the same day. Now they are under threat again. The family we talk to are 15 people living in two rooms, forbidden to have a kitchen. An electricity pylon has been built on their land but only supplies A'idi. This family tells us, "They brought electricity, water, roads, a school, a swimming pool, but to us they said 'You mustn't build or repair anything'. Our sons can't marry. All this land is ours, but they forbid us to build, and they imprison people who publicize these things". A complicated court case is going on. On another side of Shafr Amr, Hara Shihab and Hara Funyer, olive groves have been confiscated for another settlement. Displacement continues everywhere you look. ......................... At the Tawfiq Ziyad Cultural Centre in Nazareth, I attend the meeting to announce the legalization of the Council for the Defence of the Uprooted. The Centre is housed on the second floor of an old house on Casanova Street. It used to belong to the Fahoum family, and has beautifully decorated high ceilings. The only other woman present is Tawfiq Ziyad's widow. I meet Wakim Wakim, who invites me if I stay longer to meet him in Mi'ilya. Born after 1948, he seems to have little interest in al-Bassa. There is a difference in the way exiled refugees outside Palestine and the uprooted inside relate to their villages of origin. In exile, villages have formed a basis for co-residence, mutual help, marriage, recollection, research and publishing. In 'Israel'/'Palestine', some of the young are reclaiming village origins but the intermediate generation appears more concerned with current politics than the past. Wakim introduces me to a local historian, Jamil 'Arafat, who has recorded many village and tribal oral histories. Tomorrow he will take me to his town, Mashhad, where, until two years ago he was headmaster of the boys' secondary school. |

Rawiya Saffouri Shanty with her son |

[Umm Ra'ed] [Umm Riadh 'Arafat] Copyright©2005 |

|