|

Reminiscences of an alumnus

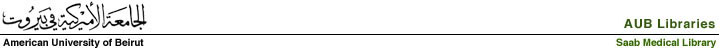

Tamer Nassar

|

A.U.B.

in the Early Thirties

Its Golden Age

by G. Fawaz Ph.D., M.D.

|

|

Oft in the stilly

night

Ere slumber's chain has bound me,

Fond memory brings the light

Of other days before me.

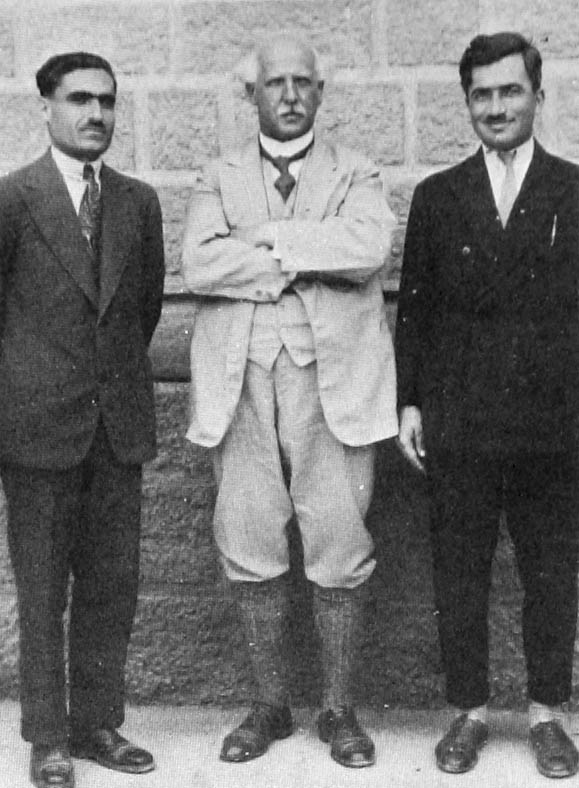

I do not recall who wrote these lines,

but I do know that when I see Mr. Tamer Nassar walking

on the Campus with his characteristic gait, "fond

memory" takes me back to the year 1929-30, when I was a

Freshman in College. Mr. Nassar then was often seen

with a strange-looking whitemaned but dignified old

gentleman who wore golf trousers on all occasions. He

was the renowned Dutch neurologist C. U. Ariens

Kappers, who even now is often quoted in world

scientific literature. Medical students told us that

Dr. Kappers was so fond of his young assistant that he

would not allow his photograph to be taken without

having Mr. Nassar beside him.

In 1932-33 when I was a firstyear medical

student, Mr. Nassar assisted Dr. Shanklin in teaching

us embryology and histology. These were the days when

the teaching staff of a medical science department

consisted of a professor and an instructor.

To look back now at A.U.B. in the early

thirties, it would seem in retrospect that that may

well have been the golden age of this 120-year old

institution.

The catalogue of the scholastic year

1929-30 shows that A.U.B. had 564 students in Arts and

Sciences, 107 in Medicine, 30 in Pharmacy, 11 in

Dentistry, 50 in Nursing and 30 in the Institute of

Music, a total of 801. There were then no schools of

Engineering and Agriculture. A.U.B. was one large

congenial family and was administered as such. It was

truly regional. The freshman class that year consisted

of 215 students, 40 of whom were Lebanese. The rest

came from Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Iraq, Transjordan,

Sudan, Aden, Persia, Ethiopia, Cyprus, Turkey, Bahrain,

U.S.A. and Sweden. Together the students and faculty

represented over thirty nationalities.

|

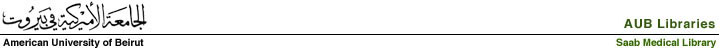

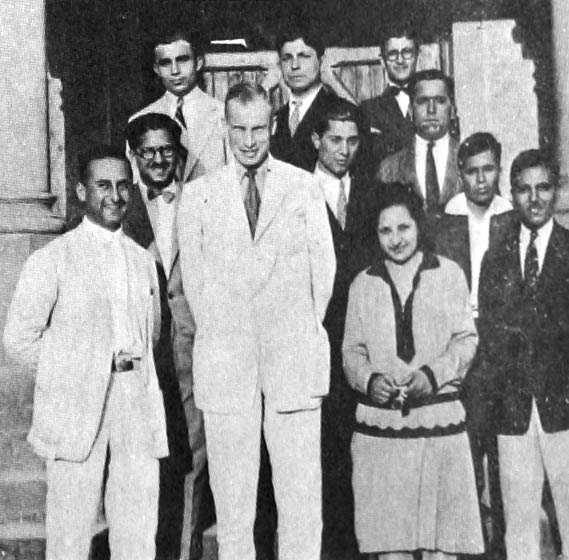

| The Brotherhood Society Cabinet,

1934-35.

|

|

|

Lebanese students came from all parts of

the country. They were natives of mountain villages or

towns along the seashore like Tripoli, Byblos, Beirut,

Sidon or Tyre. The mountain villages in the North, East

and South, even the far ones like Kfeir, Hasbaya,

IbI-as-Saki, contributed their share of students and

teachers to this institution and were part of the

cultural revival that took place in this part of the

world during the nineteenth century.

No wonder that we were constantly

reminded of the words of Daniel Bliss, spoken at the

laying of the cornerstone of College Hall by William

Earl Dodge in 1871: "This College is for all conditions

and classes of men without regard to color,

nationality, race or religion."

Even our small A.U.B. handbook

which we always carried in our pockets reminded us of

this. It contained such songs as the Cedar Song

with the chorus beginning thus: "Sing to our Alma

Mater, Queen of the East is she," or the

Al-Kulliyyeh Song which ended thus: "Living as

brothers, whether Arab, Greek or Turk, We're all for

A.U.B."

There were many societies on Campus. The

most important was the West Hall Brotherhood, a

joint faculty-student enterprise which in reality was a

living miniature of A.U.B. It carried the motto: "The

realm in which we share is vastly greater than that in

which we differ," and was a utopia, but one that

worked, at least as long as it lasted. The president of

the Brotherhood was chosen yearly from among the

prominent members of the faculty, such as Dr. Dorman,

Prof. West or Prof. Zurayk.

The Brotherhood comprised many active

committees such as the Social Service Committee

which catered even to homeless street boys of Beirut.

The Deputations Committee sent out teacher-student

groups to visit high schools in this and neighboring

countries to inform prospective students about A.U.B.

The Freshman Week Committee entertained Freshman

students and made them feel at home on arrival in

October. The Social Committee arranged for

social gatherings of all sorts and among other things,

maintained a house in Antilyas where any group of

students or teachers could hold a seminar during the

weekend. The philosopher-psychologist Laurens Seelye,

for example, would take one of his classes there and

reflect on the "deeper issues of life."

Other societies like the Youth Service

Club (at one time headed by the late

Ismail-al-Azhari who later became Prime Minister of

Sudan) and the Students Union followed programs

similar to those of the Brotherhood. Then there were

many active literary societies such as

Al-Urwat-ulWuthqa.

Teachers were accessible to students at

any time and without previous appointment. Teaching was

of a tutorial nature, in practice if not in name.

West Hall, a gift of Cleveland Dodge,

father of Bayard Dodge, one of A.U.B.'s presidents, was

named after the eminent mathematician Robert West whose

son William was later a professor of Chemistry for many

years. West Hall was not only a students' union as in

other American universities, but much more. If any one

building could claim to be the cultural and spiritual

center of Beirut, it would certainly be West Hall. It

housed the Institute of Music which gave a three-year

course that ended with a diploma conferred during

commencement. The Music Institute was affiliated with

Alfred Cortot's Ecole Normale in Paris, and Cortot

himself once came to Beirut to give a piano recital in

the West Hall auditorium.

|

|

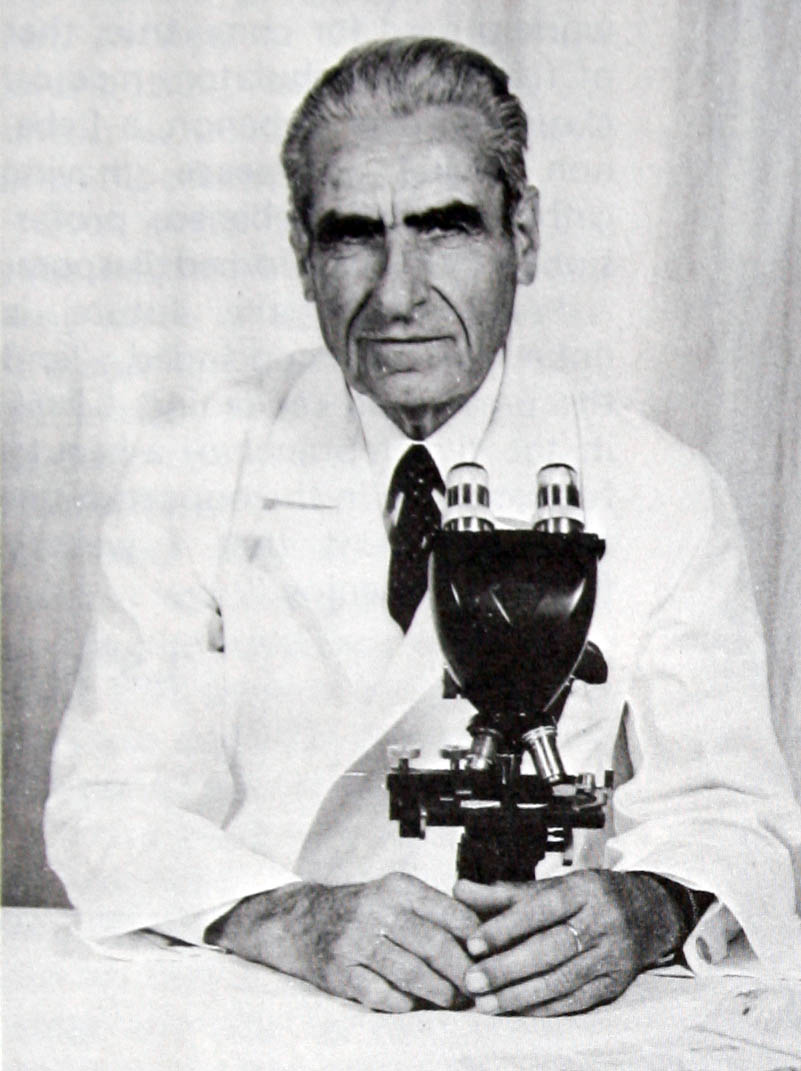

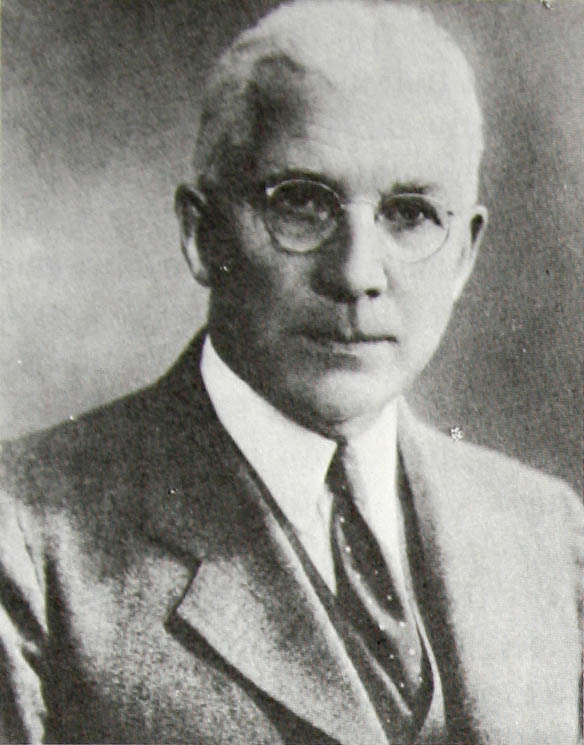

Bayard Dodge , President

1923-1948.

He seemed to be receiving when he was giving.

|

|

Every Saturday afternoon we listened to a

concert in the auditorium. One week it was a symphonic

concert, the next week chamber music. Many dignitaries

honored us with their presence and President Dodge had

a special row of comfortable chairs installed for such

VIPs just below the beautiful gallery that no longer

exists. Once, during the academic year 1931-32 when

President Dodge was on furlough and the Secretary of

the University, Mr. Stewart, replaced him,no less a

person came to attend the concert than the wife of the

French High Commissioner. She arrived about ten minutes

late and the concert had already started. Luckily, the

first item on the program was a 'petite suite' and she

had to wait outside only a minute or two. Yet she was

furious and she even cried. As luck would have it, I

was the first to suffer from her wrath s.ince I was an

usher outside the front door.

"Why did you not wait for me," she asked

(in French), "You knew I was coming, n'estce pas?"

I said nothing, of course. Mr. Stewart

tried to appease her during and after the performance

but I could see he was not successful. I cannot prove

it, but I firmly believe that had President Dodge been

there he would have waited for her. One of my

classmates who was also usher said to me the next day,

"You are an ass! If I were you, I would have told her,

'Madame, your husband represents democracy in this part

of the world!' " I retorted, "It is not too late. Why

don't you write her a note to this effect?"

But we had to pay a heavy price for

insulting Madame le Haut Commissaire. During the

commencement of June 1933 held on the Hockey Field, now

called The Oval, the audience had to wait for thirty

minutes until the Marseillaise ushered the delegate of

the Haut Commissaire, namely his secretary. His

Excellency, although a frequent guest at the Universit

St. Joseph never condescended to visit A.U.B. I rarely

felt so humiliated in my whole life! We often scoff at

the inefficiency, even corruption of our present

rulers, but they are our own people and we can vote

them out of office. There is nothing dearer than

freedom, especially independence from foreign rule.

Bayard Dodge (A.U.B. President from 1923

to 1948) never complained about it, but I have every

reason to believe that he had as much trouble with the

French mandatory authorities in Beirut as his

predecessor and father-in-law Howard Bliss had with the

Turkish rulers during World War I. Even our Lebanese

students studying at the French Medical School during

the thirties felt incomparably superior to us. "There

is no such thing as American medicine," they would say.

"One may talk of American technology, but not of

American culture."

But French men of medical science were in

a state of hibernation in the thirties; they were

resting on the laurels earned by Louis Pasteur and

Claude Bernard in the 19th century, while their

American colleagues were working diligently to lay the

foundations for a golden age of science.

After World War II a scientific explosion

took place in the U.S.A. At present, the march of

science there may be likened to an avalanche,

unprecedented in the history of mankind. To test my

contention, all one needs to do is to count the number

of U.S. Nobel prize winners in medicine, physics and

chemistry since 1946 and compare it with the number of

Nobel laureates in France or even in the rest of the

world. Even Lebanese graduates of French medical

schools are now modest and gracious enough to seek

postgraduate training in the U.S.A.!

Back to West Hall. It was not only a

cultural center but one of architectural beauty too. So

was the neighboring Jessup Hall before both buildings

were mutilated in a "renovation" process at the hands

of architects who received their diplomas from

Barbaryland. Fortunately, other buildings like Dodge

Hall, College HaIl,the Chapel, Post Hall, the old

Medical Building, Fisk Hall and Bliss Hall at least

retained their outside appearance, though most were

mutilated from the inside. So was, for instance, the

stately marble-floored office of President Dodge in

Dodge Hall, with life-size portraits of the

philanthropists who supported the Institution. This

once great office is now a kitchen where onions and

potatoes are peeled and from where the smell of roasted

meat emanates to the rest of the Campus. How easy it is

for man to bury and forget the past, even when that

past is adorned with glory and accomplishment!

Mrs. Dodge herself saw to it that the

buildings were kept clean and in good order. She paid

daily visits to West Hall, and supervised the staff tea

which took place every afternoon in the staff lounge.

Once a month, tea was held at Marquand House, the

President's residence, and if a staffite failed to

appear, he was sure to be gently rebuked later by Mrs.

Dodge: "We missed you on Friday afternoon."

|

|

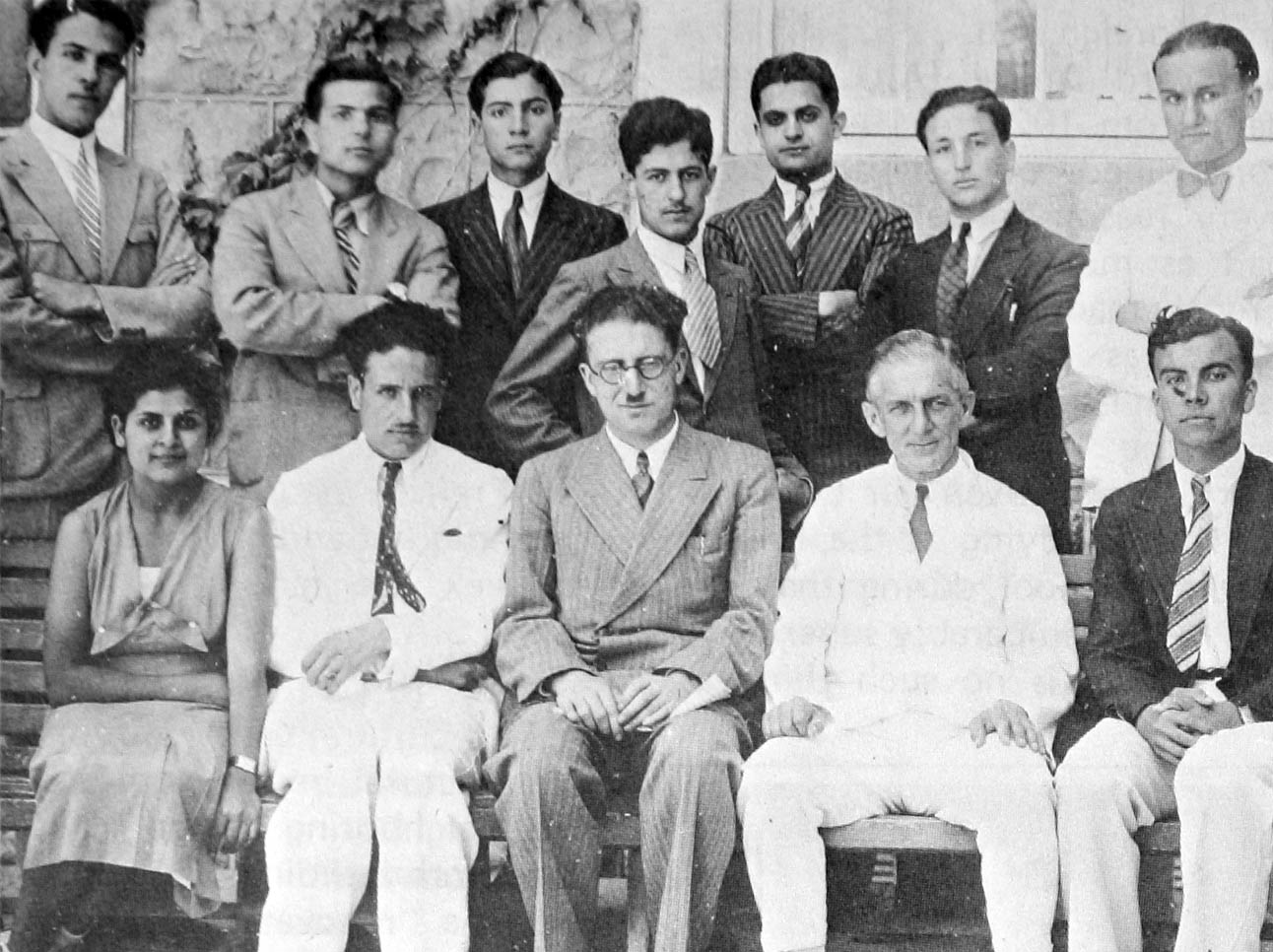

Edward E. Nickoly, the

Iron Dean.

|

|

Three bedrooms were also available in the

uppermost floor of West Hall for visiting alumni, who

were made to feel at home in their old Alma Mater.

During commencement week, an alumni banquet was held in

West Hall's Common Room, and alumni marched in the

commencement procession ahead of the graduating

students, so it was not uncommon to see father and son

walking in the same procession.

Only a handful of guards, gatemen and

gardeners were needed to maintain the Campus beautiful

and clean. No papers, empty bottles, tins or cigarette

butts were strewn on the grounds. The ever-watchful

dean of Arts and Sciences saw to it that law and order

were maintained. If a student was seen loitering

outside the Main Gate he was advised to make better use

of his time by visiting the beautiful library in

College Hall. What would Dean Nickoley think were he to

see hundreds of students idling for hours on the steps

of West Hall!

The President employed only one

secretary, an efficient but stern British lady who also

did all the work now performed by the Personnel Office.

She also protected the President against unwelcome

visitors. Once, a staffite took it upon himself to

"visit" the President, only to be turned back with the

remark: "The President is too busy to see people like

you." The President often typed his own letters and

memoranda and so did Dean Nickoley. There was no

purchasing department. All business matters including

local and foreign purchases were handled by the

University secretary-treasurer assisted by three or

four employees. The Registrar's Office was run by two

or three employees. The President ran the University as

though it were his own home, and the yearly deficit was

made up by payment from his own pocket. The University

was beholden to no government and the U.S. consul in

Beirut was treated on the Campus as politely as the

Egyptian consul. In other words, A.U.B. was meant to

teach and not to reduce unemployment in Lebanon.

The attitude of the students was, in

general, exemplary and left little to be desired. After

a long war, students wanted to make up for the time

wasted without proper schooling. They were just thirsty

for knowledge! They felt privileged to be college

students. Unfortunately, education was expensive and

only sons of rich parents could afford it, as one

needed 80-100 gold pounds a year, a sum of money with

which one could buy half a house in Ras Beirut.

Nowadays, students feel it is their right to study at a

private university like A.U.B. and if they have no

money, some students feel that A.U.B. is obliged to

secure the money required to teach them. Some students

feel they are doing their teachers a favor by attending

classes and still others choose as their motto the

familiar phrase coined by the late Dean Nickoley:

"Teach me if you can!"

Bayard Dodge's wisdom enabled him, during

the years of his presidency (1923-48), to keep A.U.B.

out of politics altogether. To this effect there was an

unwritten agreement between him and the students. His

arguments were simple and convincing:

While a student is still on the campus,

he can study political science in preparation for a

political career. The many literary and cultural

societies and clubs in A.U.B. were operated according

to recognized and democratic principles, and a student

could learn such democratic 'techniques' as Robert's

Rules of Order, etc. However, the actual practice of

politics was prohibited on the Campus and could take

place only after graduation, when alumni return to

their respective communities.

It is idle to think that President Dodge

took these measures in order to avoid conflict with the

French mandatory authorities. It is my firm conviction

that if Bayard Dodge were president of A.U.B. today, he

would keep it as uncontaminated by politics as during

the twenties and thirties of this century. He would not

allow any government, local or foreign, or any

political party to have a say in the running of the

Institution.

This was the paradise which I entered in

October 1929 coming from the American Merj High School,

a small piece of real estate (less than 2000 sq.m.),

consisting of a church that served as the main study

room and five or six adjoining recitation rooms. But it

is not the building that counts since, according to

Schiller, "it is the mind - or the spirit - which

builds for itself a body." The school faculty was of

high caliber and headed by a great disciplinarian and

pedagogue. K. Kurban, a graduate of S.P.C. and a

product of Howard Bliss's schooling. He Prepared us

adequately for later study at A.U.B. Besides, I had

received enough information about the College and

Medical School from my father and two older brothers.

The names Bliss, Dodge, Van Dyck, Post, Webster,

Graham, Adams, Moore, Day, West, Close had been

familiar to me since my early childhood. Thus the

transition from high school to college was as smooth

and natural as could be and I enjoyed my years at

college immensely.

On the day of my arrival, while standing

inside the Main Gate with some older students including

KhaIiI Wakim, of Mayo-Clinic fame - the President

whisked through coming from the outside. He stopped to

shake hands with every one of us making a few pertinent

remarks. I had seen him in photographs but never in

person. What a majestic figure! An aristocrat if ever

there was one, and a man of God, meek and humble. Our

headmaster in high school had seen him in action

helping needy people when, during World War I, hunger

and illness were devastating the country. He had told

us Bayard Dodge reminded him of John Henry Newman's

words defining a gentleman: "He seems to be receiving

when he is giving."

Two other prominent figures on the

Campus, E. F. Nickoley and L. H. Seelye, I had already

seen at the High School Conferences in Sidon and

Baalback, 1926 and 1928 respectively. Nickoley was the

Iron Dean of Arts and Sciences and is still remembered

as such to this very day even by the ordinary people of

Ras Beirut. He was respected, even feared but loved by

all students. But I never feared him, as I had realized

early in the game that the man possessed a sense of

humor but so subtle that not everybody noticed it. The

famous physiologist Hermann Rein once said that a good

sense of humor is an indication of good mental

health.

In the summer of 1934, the Social

Committee of the West Hall Brotherhood asked me to plan

the usual Freshman Week for new students, a week which

was meant to acclimatize students to the A.U.B.

environment. I chose ten older students to act as

guides in this program and presented the list to the

Dean for approval. He agreed to all except the only two

who came from my own district, one being the late W.

Mitri, so well-known in recent years for his social

service activities. In planning the very last evening

before classes started, I thought of offering the new

students a unique type of entertainment. Four speakers

were chosen to entertain the new class: a senior

student, Farid Yaish, a graduate assistant, Fuad

Mufarrij, an instructor, Afif Tannous and the last

speaker, the Iron Dean himself! I went to him and was

brave enough to ask him to be so kind as to tell the

boys how he himself felt when he began his Freshman

year at college. "The idea," I said, "was to make them

not only relax but, if possible, to laugh." When he

answered, he did not look at me but smiled at the

floor: "Yes, yes, you mean instead ot heavy advice."

That evening was a great success; all speakers did

well, especially Afif Tannous, but the Iron Dean outdid

himself. He not only did what he had been begged to do,

but promised to be the 'godfather' of the class, and

that for a good reason. He said that in June 1938 he

would "graduate" with them, that is retire. His last

words were: "Till then, let us do a good job. Let us

make it." The effect on the morale of the class could

well be imagined. But alas! our good Dean did not live

till 1938. He did not make it.

A few days after that memo. rable

evening, Dr. Nickoley met me on the road near Marquand

House. He stopped me and said: "I want to offer my

special thanks to you for what you have done for the

new students. I did not thank you in public as I knew

you would feel embarassed."

In the spring of 1935 when he knew I was

preparing to go to Europe for further graduate work,

he, without being asked for it, wrote for me a

recommendation along with a note saying: "This may be

of use to you." A couple of years ago, I discovered

that original recommendation among my old papers, grown

yellow with age. I have been asking myself since then

whether I deserved it. So this was our "Iron" dean!

|

|

Philosophy class 1929.

L. to R. First row: Afif Tannous, Laurens Seelye, Alice

Tean, Zeine Zeine. Second row: A. L. Tibawri, between

Seelye and Teen. Third row: Abdul Rahman Barbir, John

Mirhij.

|

|

Another unique and extremely popular

personality on the Campus was the towering Laurens

Hickock See lye, Professor of Philosophy and

Psychology. He was over seven feet tall and a student

once enquired about the weather at the level of his

head! He was known for his originality, and once while

talking in Chapel he tore into shreds a 25piaster bank

note in order to illustrate a point. At that time you

could buy a kilogram of meat for 25 piasters! When he

spoke he magnetized and captivated his audience. He was

a great actor and you could not but note every word he

uttered. But he always had something to say, a message

to transmit. Even when he prayed he was original as

when he started with the phrase: "Great spirit of

life." He taught me social science during the Sophomore

year. However, philosophically inclined students like

Dr. Zekin Shakhashiri - a native of AlKura, cradle of

wisdom and philosophy - who took philosophy courses

with Seelye thought very highly of his philosophy.

Seelye held another prestigious post

which had been occupied by Bayard Dodge himself before

he became president, namely the directorship of West

Hall. For if West Hall was the cultural center of

Beirut, it needed an able head, and Seelye was one.

I recall how, at the end of one year, he

was taking stock of personalities of international fame

whom he had invited to A.U.B. to talk to the students:

people as different as a certain bishop who had been

chaplaingeneral of His Majesty's forces in World War I,

and, believe it or not, Gene Tunney, the World'

heavyweight boxing champion! It certainly takes a

Seelye to invite Tunney to talk to students at the

Sunday evening service in Chapel! But I never in my

life saw Chapel as crowded as when Tunney spoke. In his

speech, Tunney said among other things that he

considered Jesus a sport!" But it is a mistake to think

that Seelye collected his speakers only from among

visitors to Beirut. He invited them from all corners of

the Globe and found donors to fund such

lectureships.

The assistant director of West Hall was

none other than Dr. Zeine N. Zeine, our esteemed

Professor Emeritus of History. Zeine was polyvalent

when he started teaching. He taught me sociology and

chemistry in Freshman. During Sophomore year he taught

me social science, a multiauthored course planned by

Seelye and Nickoley, and certainly the best course I

enjoyed in Arts and Sciences.

Zeine was also Chairman of the West Hall

Ushering Committee and his love of law and order made

him constantly remind us that the Ushering Committee

was a semi-military organization! That may well be a

reason why he specialized in the history of the Ottoman

Turks! In 1968, he took my photograph in his office on

the fourth floor of College Hall, making sure that two

rows of color portraits of the BeniUthman Sultans

appeared in the background. But the Chairman of the

Ushering Committee promoted me from subaltern to

lieutenant and when my turn came to be head-usher I was

a medical student. I had to resign, realizing that

ushering and anatomy were incompatible. Zeine was one

of our most inspiring teachers and he continues to be a

great source of counsel to his many friends and

admirers.

I said that the transition from high

school to college was pleasant and smooth. It

represented a promotion. Unfortunately, the same cannot

be said of the change from Arts and Sciences to the

school of Medicine: it was a traumatic demotion, back

into the elementary school! This was on account of

gross anatomy and the way its chairman conducted the

teaching of that course. During our last year as

chemistry majors, we were treated by our three main

professors, Drs. Close, West and Constan, not only as

graduate students but even as colleagues. They were

scholars with an exquisite sense of humor, particularly

the shy professor West. I was also introduced to Dr. S.

E. Kerr the eminent biochemist who got me interested in

some fascinating problems he was trying to solve.

Now we were suddenly confronted with the

cadavers of anatomy which, with regard to color and

consistency, reminded you more of mummies than patients

on the operating table or even dead people being

autopsied. The Professor of Anatomy, as he liked to

call himself, had the appearance of a handsome Roman

emperor and he was well aware of it, for he acted like

one. I never saw him laugh, though he occasionally

smiled, condescendingly. You could not relax in his

presence, as any innocent remark could produce a

violent reaction on his part. When it pleased him to

attend the daily Chapel services, he sat on the

platform in the front row and, when possible, right

next to the President, although the front row was

reserved for full professors and he was an associate

professor. He would sit for full 20 minutes like a

statue, so much so that once our late witty pathologist

Nimr Tukan shouted to him in Arabic across the audience

"Taharrak! Move and show us you are alive!" Some

thought he was best suited to be an army general and,

indeed, he concluded his career in the armed forces of

his country. He studied medicine at the University of

Michigan and was convinced that there was no place on

earth where anatomy was better taught. He even founded

a "Michigan Club" at A.U.B. for teachers who had

studied at Ann Arbor! He thus introduced the Michigan

dissection manual of his illustrious teacher.

This is the manual which starts with the

Trapezius, Latissimus dorsi, Multifidus and

Sacrospinaus. How many precious hours were spent

learning the origin, insertion, nerve supply and action

of the Sacrospinalis in its three columns and various

parts of each column! But the Professor of Anatomy kept

repeating: "Gray's anatomy is a reference book; you

only need to learn what is clinically significant." We

soon learned, however, that the structures of clinical

significance were those which he happened to remember.

If, in the course of the dissection he came across a

small vein which he knew, then that was truly

significant; yet if he stumbled across a big artery or

nerve which he could not identify, then it was of no

clinical value.

Our Professor of Anatomy was convinced

that gross anatomy was the most important subject in

medicine. It was taught in Med I as Gross Anatomy, in

Med II as Topographic Anatomy, in Med Ill as Applied

Anatomy and in Med IV as Surgical Anatomy. I used to

read the examination questions of the advanced courses

and concluded that a first year student in June could

answer all those questions.

This reminds me of Dr. Bahij Azouri's

French teacher in Sidon who said to his students,

"Boys, we have two courses for supper tonight: Mikta

salata and Mikta arsh." During the recitations there

being no lectures - the professor would ask a student

to describe a structure while he stood at the window

gazing at the courtyard of Van Dyck Hall. As long as

the student kept talking all went well; he could say

the most absurd things on earth. But if he got stuck,

the professor would scold him as though he were a

student in a village elementary school. So the students

drew their conclusions early in the game: Take no

chances; memorize Gray thoroughly. It was indeed a

remarkable feat, but at what expense! As far as I was

concerned, the trauma to my memory proved to be

irreversible!

The Professor of Anatomy had two

associates in 1932-33, both natives of Al-Kura. Of the

two, the junior associate had a more delightful Kurani

accent! He preferred Cunningham's textbook to Gray and

while dissecting he would ask one of the students to

read to him from Canninhan.

The senior associate, M.D. 1928 (with

distinction) soon became a better anatomist than his

chief. There was no structure, no matter how small,

that could hide long from his probe, so he was the

undisputed 'master of the probe.' He also had a

phenomenal memory. Once, one of my brilliant classmates

spent a week to learn the most difficult assignment in

anatomy, namely the temporal bone, only to discover

during the recitation period that the 'senior

associate' knew it better.

The junior associate, M.D. 1931 (with

distinction), had his own way with the boss. Yet, he

learned and required from his students as much anatomy

as was required for general medical practice. He was

not like a bamboo cane, that would be swayed by a burst

of breeze, but more like a lofty mountain that could

not be shaken by a storm. He is our emeritus professor

of anatomy, still in private practice, and one of the

best - if not the best family physician in Beirut.

How did the Professor of Anatomy get

along with his colleagues, heads of the other medical

science departments? One of the senior professors said

to me a few years later, "The only way to tame the

anatomist and thus have peace during the Preclinical

Committee meetings was to elect him as chairman of the

committee!" How true to life! Did not Neville

Chamberlain tame Adolf Hitler in 1938 by offering him

the Sudetenland and thus achieve 'peace in our time,' a

peace that lasted exact. ly one year? Professor Seelye,

in his psychology course, described some teen-agers as

rebellious adolescents. Some rebellious adolescents

never mature and they usually have their way in life.

Everybody wants to avoid a confrontation, nobody wants

to have a "scene," hence "laissezfaire.

I have gone into so much detail

describing our 'professor of anatomy' because such

characters are found in abundance, especially at

universities. Not long ago, a visiting Oxford scholar

described a university as a collection of eccentrics.

Furthermore, I personally feel guilty because we are

doing to our medical students what our "professor of

anatomy" did to us, except that we have substituted

Goodman and Gilman and Harrison for Gray.

We teach medicine during four years

instead of five (as in the thirties) although

accumulated knowledge in medicine has grown

astronomically. We require so much detailed knowledge

because the students have to sit for the National

Board, ECFMG, VQE and RSVP examinations, the questions

of which may have been prepared by professors who had

studied "in Michigan!' I predict we shall soon witness

a revolution in medical education.

The course in biochemistry to which I had

been looking forward after my brief contact with Dr.

Kerr also proved to be a disappointment, although I

thoroughly enjoyed the laboratory part planned so

carefully by Dr. Kerr. Dr. Kerr was on furlough that

year and he was replaced by a visiting professor,

allegedly a great man because he was author of a

textbook of biochemistry widely used but deplorably

uninspiring. The professor from Galveston, Texas spent

the first semester reading to us verbatim from his

textbook and I can swear that my biochemistry lecture

notebook remained a blank. What a waste of time and

money, and what a difference between him and Kerr who,

as I found out when I was his graduate student, made

even undergraduates feel as though they were not only

witnessing but also assisting in the birth of an

epoch-making discovery!

During my years with Dr. Kerr, he, like

his own teacher in Philadelphia, spoke disdainfully of

people who do nothing but write textbooks. Needless to

say, there are people who are both good

experimentalists and writers of monographs and

textbooks.

At the end of the biochemistry course in

February and just before the final examination, the Med

I students held a farewell reception in West Hall in

honor of the visiting professor. Dr. Dorman, head of

Obgyn, made a short speech in which this exchange of

professorships was described as unique in the history

of medical education. How untrue, I reflected. In

reality there was no exchange. At that time Dr. Kerr

was at Harvard Medical School where he succeeded in

demonstrating the presence of phosphocreatine in brain

tissue, and isolating the substance in Beirut a year

later.

Even the course in physiology was not a

success. It made me lose my enthusiasm for physiology

and, to revive it, I had to wait for several years till

I studied it under Hermann Straub (the internist) and

Hermann Rein at the University of Göttingen. The

physiologist at A.U.B. meant well but he was very

limited. I was sorry for him because I felt he was

unjustly persecuted by both faculty and students.

|

|

Dr. Kappers. At his

right Tamer Nassar

|

|

This leaves us with histology, which,

like physiology, was given in the second semester

anatomy, being anatomy, was given all year round - and

we thus return to where we started, to our dear Mr.

Tamer Nassar.

What we now call the department of human

morphology consisted then of two departments: gross

anatomy, histology and neural anatomy. The head of the

latter department was a godfearing, honest and modest

scholar. He always reminded us that he knew no more

histology than we did. His strength lay in comparative

neurology. Dr. Kappers also infected him with his own

hobby, anthropology, and like Dr. Kappers, he measured

skulls of people and also made some students like me do

the job for him. As a neurologist, however, he was

particularly fond of the brain of the chameleon and was

recognized as the world authority on that subject. He

talked so fast that he often swallowed syllables or

even words. If he asked you to identify a structure

under the microscope meaning to say: "What is that at

the tip of the pointer?", you heard only the word

pointer. When he pointed to Mr. Nassar's laboratory

adjoining the student's lab he said, "Mister Sore's

office." And to this very day I greet Mr. Nassar as

Mister Sore. It is very difficult to describe Mr.

Nassar and do him justice. Not only was Dr. Kappers

fond of him, but so were all students and faculty as

well.

Mr. Nassar reminds you of the words of

Goethe: "Edel sel der Mensch, hilfreich und gut."

(Noble be the human being, benevolent and good.)

Nothing pleases Mr. Nassar more than to be able to

assist a student in despair. He is always smiling,

composed, soft-spoken and I never saw him lose his

temper. The laboratory sessions in histology were not

only a pleasure for us but a relaxation as well. But it

is a mistake to assume that Mr. Nassar was less

demanding than other teachers. No student was allowed

to leave the laboratory before completing the

assignment satisfactorily. Three of us, the late Drs.

Hassan Idriss and Shukrallah Karam -author of the

familiar saying, "If the patient recovers, it is due to

Allah, but if he dies it is the fault of Shukrallah" -

and I were close friends and competitors as well. We

were seated together, right next to Mr. Nassar's

office. We used to finish our lab work early and demand

from Mr. Nassar a "bonus." To us, this meant a

collection of beautiful slides which Dr. Kappers had

bequeathed to Mr. Nassar. It was intended to test our

diagnostic abilities, and we appreciated the special

attention paid to us.

But Mr. Nassar could also cheat! The

laboratory part of the final examination consisted of

some twenty slides which he had just prepared for that

purpose from animal material. I had difficulty with one

slide and was annoyed. It consisted of nothing but

connective tissue! I complained to Mr. Nassar: "This

slide cannot be part of Dr. Kappers legacy." Mr. Nassar

looked at the slide, moved it, then left without saying

a word. When I looked again I saw, at the tip of the

pointer, cartilaginous tissue and realized I was

looking at a lung, but it was anything but typical.

|

| Mr. and Mrs. T. Nassar with

children. L. to R. Nabeel

(MD '65), Hilda (Medical librarian) and Khalil.

|

|

|

Mr. Nassar was born to an old and

distinguished family in Ain-Ksour adjacent to Abey in

the Shout mountains where in 1843, long before the

founding of the Syrian Protestant College, Cornelius

Van Dyck started his Academy.

Mr. Nassar can boast of 44 years of

full-time and 16 years of part-time service to this

Institution, and this constitutes an enviable record.

He states that one of the most rewarding experiences of

his long career has been the frequent discovery that

one or more members of a new class had been children of

his former students. For instance, we have just

mentioned Drs. Shukrallah and Hassan. Well, Mr. Nassar

takes pride in pointing out that their respective sons

Drs. Karam and Ziad, both prominent physicians are,

academically speaking, and like so many other doctors,

his own grandchildren. It is this personal element, the

so-called human touch that enriches the life of a

teacher.

Here is to Mr. Tamer Nassar, may he have

a long and active life, so he may discover among

members of a future Medicine I class an academic great

grandchild.

|

|

From "SCAN" Medical Alumni

Newsletter - A Supplement of al-kulliyah

Spring 1987

Volume 5, Number 1

(AUB Medical Alumni)

The above article is transcribed

from a copy at the AUB's Saab Medical Library.

[Back]

|

|