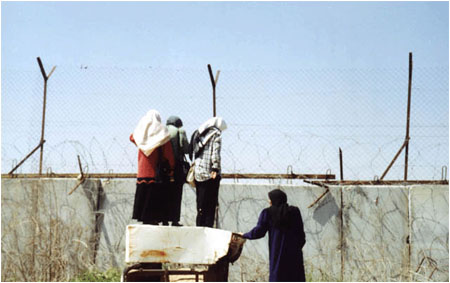

Umm Muhammad Shahada (in black) and two of their children.

|

Umm Muhammad Shahada (in black) and two of their children. |

| Umm Muhammad Shahada, Rafah camp, April 8:

|

|

Two of Abdel Salam's brothers have married two sisters. I decide to record with the older sister, Umm Muhammad, because of the number of different countries she and her family lived in before returning to Rafah after the Oslo Accords. True, only one of these moves was the result of war, but in a broader sense they showed the way post-1948 statelessness and unemployment at 'home' forced thousands of refugees to migrate in search of work.

Umm Muhammad is young middle-aged, with a lively face and easy flow of conversation. The burden of her nine children sits lightly upon her, perhaps because the eldest are girls with whom it's easy - at least on holidays from school and university - to leave the younger ones. She can be away from home for a few hours without worrying what will happen. Inside as well as outside the home, all the older women of the Shahada family wear headscarves and the long-sleeved jilbab that conceals arms and legs. My second day in Rafah, Umm Muhammad dons a blue jilbab and black head scarf to take me to view the infamous wall - called the 'silik' - that separates Rafah from 'Canada camp' on the Egyptian side of the frontier. Her parents live in Canada camp, waiting their turn for transfer back to Rafah. Every few days she comes here to shout greetings and enquiries to them across a No-Man's-Land frequently patrolled by Israeli jeeps. The wall is made of concrete blocks too high to be seen over, topped with a meter of wire fencing crowned with wreaths of barbed wire. Although it's still quite early when we reach the wall there are already several people here. The men climb spindly trees close to the |

wall, while women wait their turn to mount the carcase of a refrigerator, the only stepping stone visible on this stretch of wall. It's forbidden to place any permanent structure close to the wall. From the top of the refrigerator, you can see across the military road used by Israeli jeeps, and across more rolls of barbed wire, to 'Canada camp' about half a mile away.

Eventually a cousin shows up, and he and Umm Muhammad shout at each other for a few minutes. It's hard to hear - the distance, other shouters, the wind that carries words away - all this makes communication a struggle. The cousin urges Umm Muhammad to come over for a family wedding tomorrow. But it costs a lot to get a permit to cross the border, even to make a phone call. Umm Muhammad grew up there in 'Canada camp'; her natal family fled to Egypt during the Israeli invasion of 1967. In 'Canada Camp' no one had work. They lived under constant curfew. Kids got beaten if they were caught on the street. Since Oslo, Israel is allowing families to return to Rafah but so slowly that it will take years before all can make it. The first words of Umm Muhammad offer a striking contrast to those of her mother-in-law, Umm al-Abed. In terms of their mobility, too, their stories contrast. After the first displacement of 1948, Umm al-Abed has spent her life penned in Rafah camp. Umm Muhammad's story is marked by frequent crossings of difficult borders.

Umm Muhammad begins her story: |

Umm Muhammad Shahada waiting for her turn to call over the wall to her relatives in "Canada Camp". |

|

[Umm Jammal Bakiyya] [Sara 'Adwan] Copyright©2005 |

|