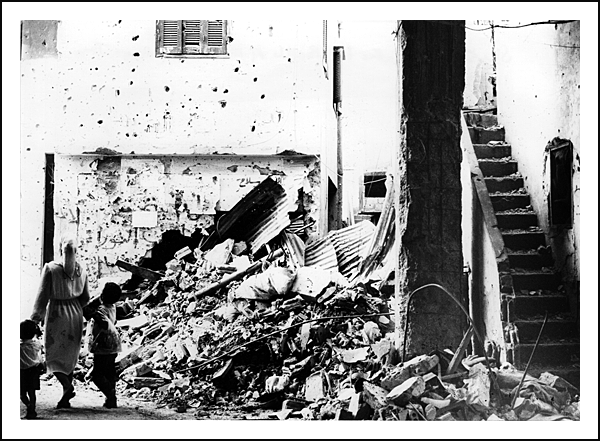

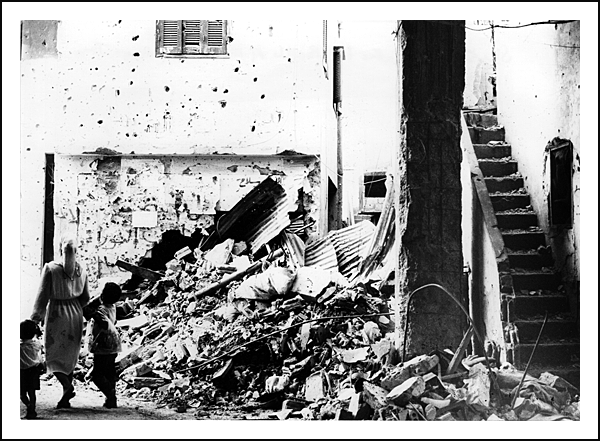

Shateela after the 1st Battle of the Camps (May - June 1985)

Photo: Rosemary Sayigh

|

Shateela after the 1st Battle of the Camps (May - June 1985) Photo: Rosemary Sayigh |

INTRODUCTION TO THE VOICE ARCHIVE WHY PALESTINIANS? WHY DISPLACEMENT? WHY WOMEN?

|

|

When I first started living in Beirut in 1953, newly married to Yusif Sayigh, a refugee from Tiberias, I knew absolutely nothing about Palestine or Palestinians. My English family was middle class Labour, oppositional and anti-imperialist. We did not go to church, and Bible stories were not part of my family background, which meant that I had none of the 'Holy Land' baggage in my head when I first went to the 'Middle East'. But I had nothing else either, no balancing knowledge of Arab history, culture or language. Both in school and at university I had Jewish friends, and in the summer of 1948 (when I was graduating) some of them were agonizing over whether they should go and fight for Zionism. As far as I knew anything at all about Palestine, it was as a place where Jews were waging a national independence struggle against the British, which as a Labourite I supported -- just as I supported the national independence struggle in India. Nowhere in our background or in our history lessons at school was there a place for the Palestinians.

It was a quirk of fate, not the pursuit of study, that took me to Baghdad in 1950 to work as a teacher of English language and literature in the Queen Aliya College. It was a college where all the students were women and all wore abbas, those enveloping black cloaks that could be made to cover everything. One of the members of our faculty was a Palestinian - the distinguished writer and artist Jabra Ibrahim Jabra - but I did not learn about Palestine from him. Talk among Iraqi friends was of problems closer to home, mainly continuing British influence over the supposed-to-be independent Iraqi kingdom, where there was said to be a shadowy British director in every government ministry. I became aware of the recent exodus of Iraqi Jews to Israel through the vast market for second-hand furniture where we English teachers bought sofas and beds. Stories of the double scandal that had propelled the flight of this ancient community |

were still fresh when I arrived in Baghdad: bombs near synagogues (eventually traced to Zionist agents) had created the necessary fear, and the corrupt son of Prime Minister Nuri Said had provided the transport, with enormous benefit to himself. Not all left, however: our monthly salaries were paid to us by a friendly Iraqi Jew in the Ministry of Finance, Edouard, who welcomed us with glasses of noomi hamudh (dried lime tea).

In Beirut, among Yusif's family and friends, I do not remember that there was much talk about Palestine, or of leaving it, though the Nakba (catastrophe) was so recent that you would expect it to have left a palpable trauma. Of course my poor Arabic must have made me miss many subtle references. But though they were such recent refugees, there was no sense of special poverty about them, or of being displaced. Thinking back about this, I realize that class and sect had much to do with it. Yusif's parents had strong links with the Protestant community in Lebanon. They had spent summers in the Lebanese mountains, to escape the heat of Tiberias, after Umm Yusif had suffered her first heart attack in 1940. Yusif himself had gone to school and university in Lebanon, as indeed had many other Palestinians. It wasn't only Christian and better off Palestinians who knew Lebanon before 1948; many kinds of exchange -- commercial, social and cultural -- linked the villages and towns of northern Palestine with those of Southern Lebanon. The national boundary created between Palestine and Lebanon by the French and British Mandates meant very little to the people living in the region. They came and went according to their needs, whether of trade, education, vacationing, or seeking brides - that is why the refugees found so many connections when they first arrived. Looking back, I realize also that I didn't know enough to ask the right questions; |

|

Copyright©2005 |

|