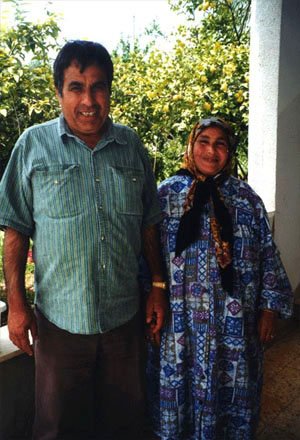

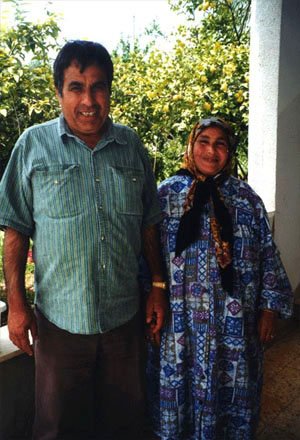

Umm Bassil with her husband (Said),

Kfar Kenna, April 2000.

|

Umm Bassil with her husband (Said), Kfar Kenna, April 2000. |

| Umm Bassil (Arab al-Sbeih), Kafr Kanna, April 17:

|

|

Finally, the Mayor comes and take us to meet one of the displaced 'Arab al-Sbeih families who are living in Kafr Kanna. We find an old lady, Umm Sa'id, and her daughter-in-law, Umm Bassil. Umm Sa'id isn't reassured by the presence of the Mayor, she speaks very guardedly - "Everything has been fine since 1948", etc. At this point Umm Bassil grabs my arm and takes me upstairs to a vine-shaded roof. There she talks about the injustices her people suffer, about being separated from their land, and stories of 1948 that she heard from her mother. Her transmission of her parents' stories of the first days after the expulsions throw light on a period that few researchers have yet touched.

Umm Bassil begins speaking:

"There's my aunt and my uncle - (Please talk about yourself first.) I am Umm Bassil Salim Ikhtawi. I married into Kafr Kanna, [a man] from my uncle's house. My mother and father used to say when I was young - I used to hear them - how her brother came to her. And her sister's husband, he came once or twice. He said, 'I need money. I'm living in the mountains, in hunger. I want to come and take my money that I hid, money and my things in Mashhad, with a friend in Kfar Kabour. Now I want my money and my belongings.' When he went to ask for his belongings, this man told him, 'Okay, I'll give them to you. Come to me on such-and-such a day' - and he gave him a certain day. And he came. Now when he came, my mother asked him, 'How's my sister? How are her children?' He said, 'They're okay'. She told him, 'We heard that some people want to arrest you, to catch you and kill you. Take care!' He said, 'Don't be afraid. I'm just here to get money to feed my children. I'm staying in the mountains, under the trees. There's nothing there. Me and my children, my brother and his children, I want to feed them'. It was after 1948. Now the day he came to take the money, they caught him. The day they caught him, the Jews denied it. They said, 'We don't have him'. But there were [other] prisoners there and he sent a letter with them, 'Oh sister! Oh brother! Find me a lawyer through the Red Cross'..." Jamil has studied the 'Arab al-Sbeih. After we leave the family in Kafr Kanna he proposes to take me to visit the village of Shibli where most of the 15% who did not go to Jordan or settle in Kafr Kanna now live. On the way he tells me some more about this group's history. Though they were permitted to stay after 1948, 'Arafat says, "There were still pressures on them. Because of the pressures, in 1952, they thought that only the Deir [Monastery] could protect them. So they went up the Tur [Tabor] mountain and asked to become Christian converts. They converted to Christianity for a short period, the whole 15% of the tribe.

|

Then when they [Israelis] left them alone, they returned to their homes. But they were not allowed to call themselves 'Arab al-Sbeih'. It was forbidden. They gave them the name 'Arab al-Shibli'. The village of al-Shibli has a relatively prosperous look. Many new houses are under construction, and some are being built in stone, not breeze-block. Jamil explains that many of the men here join the Israeli Army, as bedouin and Druze Palestinians are encouraged to do. As we drive to the home of Abu 'Issam, a local teacher, the houses thin out and become poorer-looking. Yet Jamil says this is where all the big Sbeih families had their land. Perhaps leading families were more nationalist, and that's why they felt obliged to leave after 1948?

Land was individually owned by the Sbeih - and lots of it. It stretches from the foot of Mount Tabor almost as far west as Illit (Upper Nazareth, a Jewish suburb). We go to see where the massacre took place. There's a dirt road with a barbed wire fence to stop cattle straying. A few stones of destroyed houses are visible. Abu Issam says that a contractor sold most of them years ago to 'fellahin' (peasant farmers). There's no Jewish settlement in sight. Abu 'Issam has invited a very old man, Abu Hassan, to talk to me. Jamil begins questioning him about the massacre and the 'conversion'. I don't want to record this but feel it would be discourteous to Jamil, who is giving me so much of his time, not to do so. Later Abu 'Issam takes me to meet his aunt Nadhiya. She's friendly and ready to talk, but doesn't understand my Arabic. Jamil and Abu 'Issam come to the rescue, firing questions at her one after the other, leaving her no time for reflection. It's a demonstration of masculine-style interviewing. Even after I ask them to give her a chance to speak, the recording doesn't really take off. We have lunch at the schoolmaster's house, and meet his wife who did her English BA in the United States. Abu 'Issam can remember going up Mount Tabor as a boy of four. He tells an amusing story of how the Sbeih people used to dismay the priest by mixing Christian and Muslim prayers. There's a picture of the Virgin Mary with Jesus in the lobby - maybe a residue the 'conversion' experience? Before we leave, Abu 'Issam gives me a map of 'Israel'/'Palestine' with the place names in Arabic. He says the local Council was too scared to keep it. Jamil 'Arafat drops me in Nasra. It's my last evening there. I go to the Municipal Library to say goodbye to Zuhayra. Some of the members of the cultural club she founded, 'Feneek', are there: Raji' who has made a film about Haifa, and Ghassan who is a student of Sufism. |

[Umm Sa'id ] [Monday April 18, departure] Copyright©2005 |

|