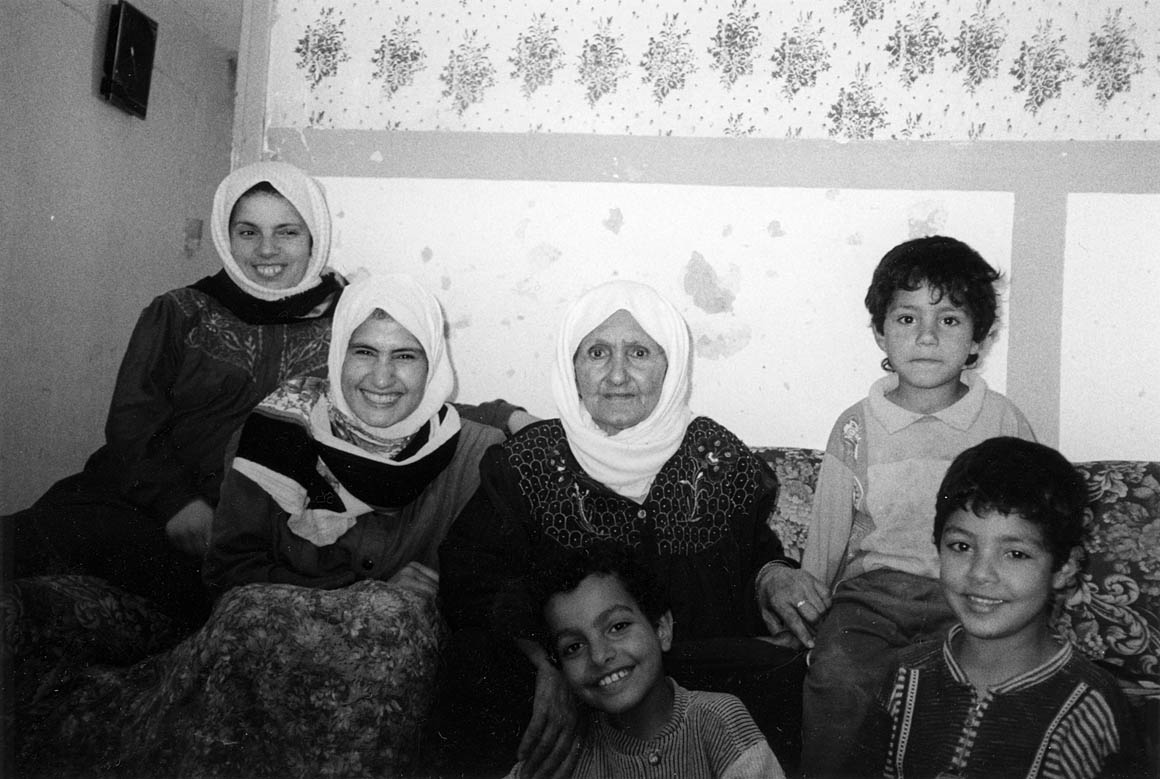

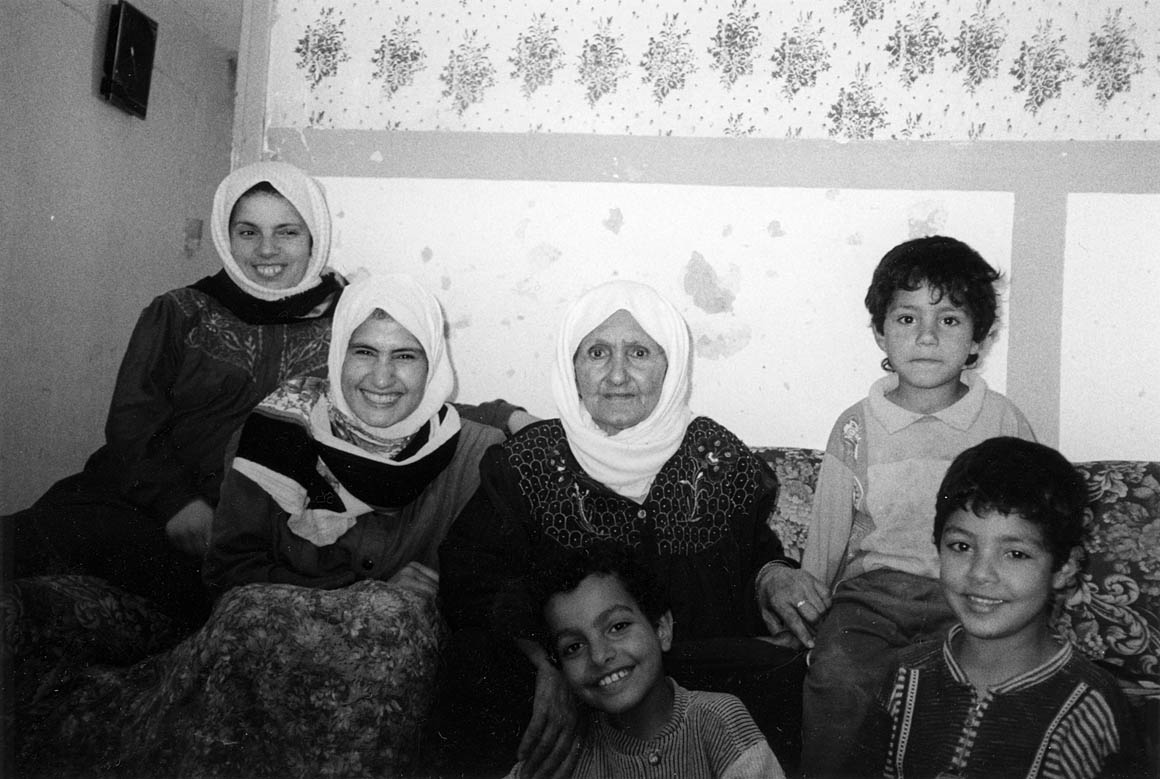

Hajji Aziza Harbi Mansour Arslan, Umm Awni, Kalandia camp

|

Hajji Aziza Harbi Mansour Arslan, Umm Awni, Kalandia camp |

| Hajji Aziza Harbi Mansour Arslan, Umm Awni, Kalandia camp, June 12:

|

|

Here I am helped to find people who have been displaced more than once by Wajih 'Atallah, a Youth Activity Centre coordinator. He has the stamp of all refugee camp activists I meet -- dynamic, well-informed, in touch with ordinary people. He's part of a growing movement to reinforce the identity and interests of camp populations in potential opposition to the National Authority, viewed as likely to brush the refugee issue under the carpet in return for a state. Part of this movement takes the form of putting refugee camps in direct contact with each other through modern communications technology, unmediated by regional states or international agencies.

Wajih proudly shows me the Centre, equipped with computers and scanner, and their logo, an open book whose leaves are coloured red, green and black, like the Palestinian flag, a football and a sun with twenty rays, one for each West Bank camp. When he understands that I'm looking for people who have been displaced more than once, he takes me to two households that came from Gaza after the 1967 invasion. Gazan refugees fled to many different areas at that time, some to Sinai, some to Jordan, some to the West Bank. Refugees in Gaza had little to lose in leaving, unlike original Gazan inhabitants, whether owners or ordinary citizens. With the highest concentration of refugees in any area, cut off from contact with other Palestinian communities, with minimal employment possibilities and excluded from emigration to the Gulf, Gazan refugees could hope for better conditions elsewhere. But, in fact, they were generally disadvantaged in comparison with already established refugees from 1948. The home of Umm Awni Arslan is just one room, divided by flimsy wood frames |

into functional spaces, and covered over with a zinco roof. Such structures recall an earlier stage of refugee existence, and point to low income, perhaps because a single 'unskilled' wage earner supports the household. Other homes in this camp are more like those you would find in low-income urban areas, with internal dividing walls and roof of cement. The birth order, gender and ability of children are key discriminators between camp families in terms of income and social status. Here daughters seem to predominate. Recording with Umm Awni, an elderly and unforceful lady, is disrupted by a crowd of noisy grandchildren whom we cannot keep out because of the 'open plan' house form.

It turns out that Umm Awni is Egyptian, and met and married her husband in Port Sa'id before 1948. He was a boat-man from Jaffa who regularly worked between Palestine and Egypt. Such marriages are not unusual -- one frequently comes across 'foreign' wives and mothers among Palestinians, evidence of the much greater freedom of movement before 1948, and the permeability of borders. A special source of suffering for such wives is physical isolation from their families of origin. One senses this in their demeanour even if they do not speak of it. Umm Awni speaks:"My husband came and we got engaged. In Egypt. In Port Sa'id. Then we came to Jaffa. We stayed in Jaffa almost five years. I had three children, Awniya, Awni and Majdiyya. Then we left and we stayed six years. Then we went to Egypt, to 'Antara, we stayed there for a year. When we had stayed a year there they took us to Gaza. We stayed in Gaza, in tents of course, they gave us things. We stayed in tents for a year. Then they provided us with houses of straw and mud. We stayed there for a year..." |

[Umm Kassem al-Azrak] [Umm Ali Muhasil Arslan] Copyright©2005 |

|